Understanding UBO structures

UBOs are often concealed by complex legal structures, which makes it difficult to identify a UBO. In this article, we will help you better understand the complexities of legal UBO structures and provide examples (halfway through the article) of different types of UBO structures.

UBO structures

UBO structures

Summary

The complexities of ownership and control

Identifying and verifying ultimate beneficial owners (UBOs) is an essential component of both the Know Your Customer (KYC) onboarding and monitoring process. Moreover, it is central to the latest set of international sanctions and regulations in the areas of Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Counter-Terrorism Financing (CTF) as well as tax compliance laws and standards such as FATCA and CRS. The impact of this on the financial sector is great, but also other organisations with Know Your Vendor (KYV) and Know Your Third Party (KYTP) obligations are affected.

While the penalties don't lie, uncovering complex legal structures designed to conceal UBOs is a huge challenge.

This article helps to better understand complexities of legal beneficial ownership structures. It also provides insight into how data and analytics can improve the speed and accuracy of UBO identification, as well as how you as an organization can benefit from improved knowledge management to reallocate resources.

Shrouded in mist

While offshore tax havens have been the focus of public anger due to numerous scandals, it took the publication of the infamous Panama Papers were the target of public anger, it took the publication of the infamous Panama Papers to show how flexible legal structures - in combination with the protection offered by offshore jurisdictions - make it difficult to identify (ultimate) beneficial owners.

To date, few jurisdictions have defined beneficial ownership. Although various regulations and standards in the areas of AML and CTF are largely unified on a definition that

Disclosure of beneficial ownership is not a new phenomenon. Legal frameworks that oversee the disclosure of ownership and governance structures have long existed as a foundation for the prevention and detection of fraud, corruption, tax evasion and criminal activity. Although most customers and third parties are legitimate businesses, terrorism and geopolitical instability on the world stage have shown how terrorists, human traffickers and corrupt officials finance themselves through financial networks. In response, governments and lawmakers have recently stepped up efforts to eliminate financial support for these criminals, including by requiring organizations to find out who actually owns the company they are dealing with and make sure they are reliable.

For many organizations, getting down to the level of detail is by no means child's play. It often takes days to identify manually entered information such as company name, address and registration details.

Read back or share this article later at your leisure?

Download it and receive it as a PDF in your mail.

A regulatory catch 22

Yet most of these sources have no or limited access to offshore entities, or they contain unreliable and incomplete data. According to the World Bank, to the extent that public registers already exist (such as the Persons of Significant Control register in the United Kingdom)

While there is a trite set of rules, it is not wise to rely on one beneficial ownership definition. For example, financial institutions of the FinCen Final Rule not to verify that individuals who are on a beneficial owner list based on self-certification are actually stakeholders of a legal entity. Without further steps to verify beneficial ownership, financial institutions may not be fully compliant with laws implemented in other jurisdictions, such as the EU's Fourth AML Directive.

The biggest challenges of beneficial ownership

- The beneficial ownership process is a huge burden on business operations.

- The lack of UBO information in public records is an Achilles' heel within the entire AML effort.

- The complexity and variety of beneficial ownership data is becoming one of the biggest challenges for companies operating internationally.

- Non-standard documentation in offshore financial centers (OFC).

- Flexible changes of ownership in OFCs.

- Various ownership layers are confusing.

- Non-cooperation, unwillingness, and default disclosures.

A risk-based approach to beneficial ownership

As the regulatory landscape and the nature of available information change, UBO identification seems like an insurmountable task. A risk-based approach with standard lower limits for UBO identification and three lines of defense strategies is standard practice for low risk compliance teams.

Beneficial ownership falls into three categories: executive directors (and/or senior officers), major shareholders (owning at least 3 percent of an organization's securities), and de facto third-party shareholders. Calculating UBO is relatively straightforward for a publicly listed company with direct shareholders.

However, it gets trickier when ownership is disguised by multiple layers of indirect ownership. These ownership structures pose hefty risks and therefore require greater diligence on the part of compliance teams so that they can demonstrate that they have taken all possible steps to identify UBO.

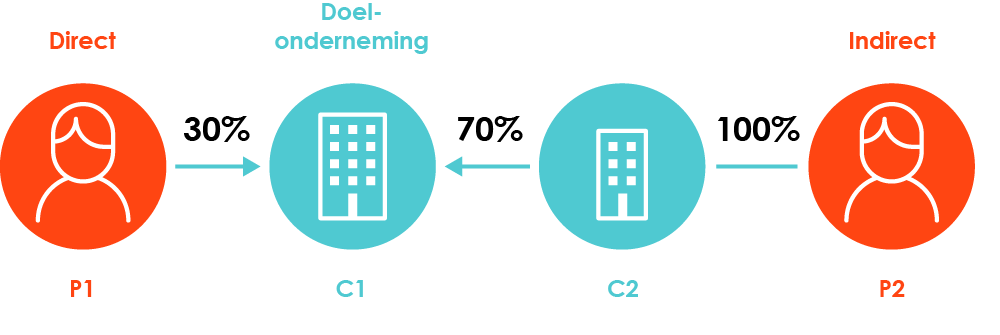

Direct and indirect ownership: put the puzzle pieces together.

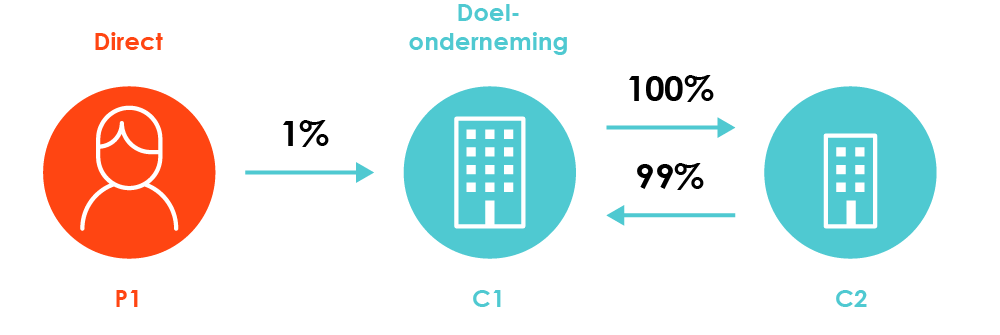

Beneficial ownership is best visualized as a series of direct or indirect relationships. In the following diagrams, we have depicted the different levels of ownership between stakeholders and entities.

Person P2 is a direct owner of enterprise C1 and posseses 70% of the shares.

Simple indirect shareholdings

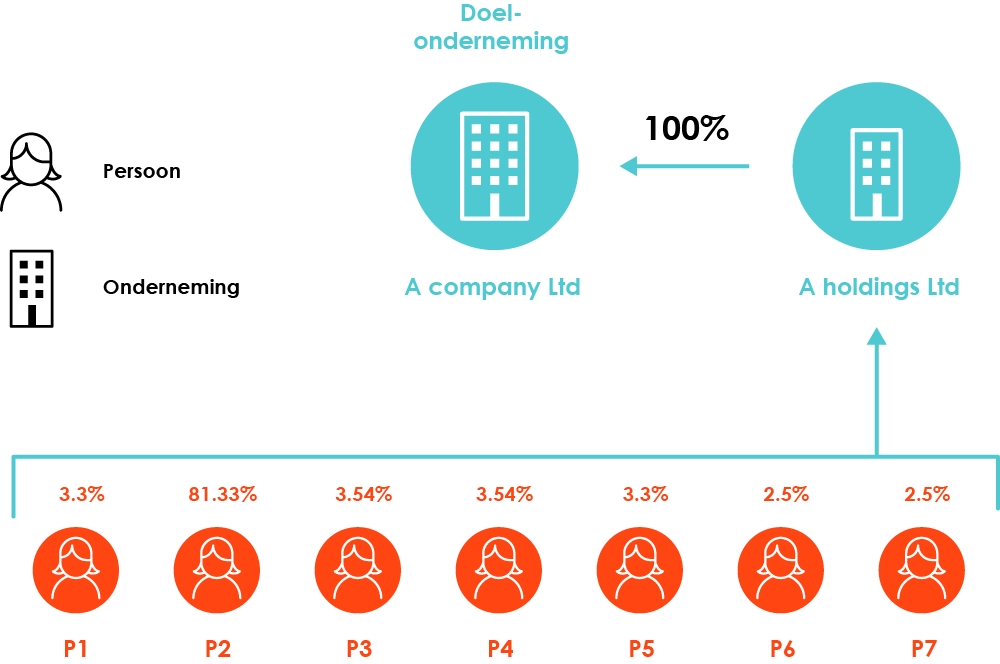

The level and lower limit of ownership that an organization wants to work with depends, among other things, on its risk appetite. Thorough identification of UBOs requires reliable information and, to the extent necessary, detailed research.

Different levels of indirect shareholding

Want to easily determine UBOs yourself?

With indueD, you do due diligence in one convenient environment. Establish UBOs and screen your clients for PEP and sanctions lists.

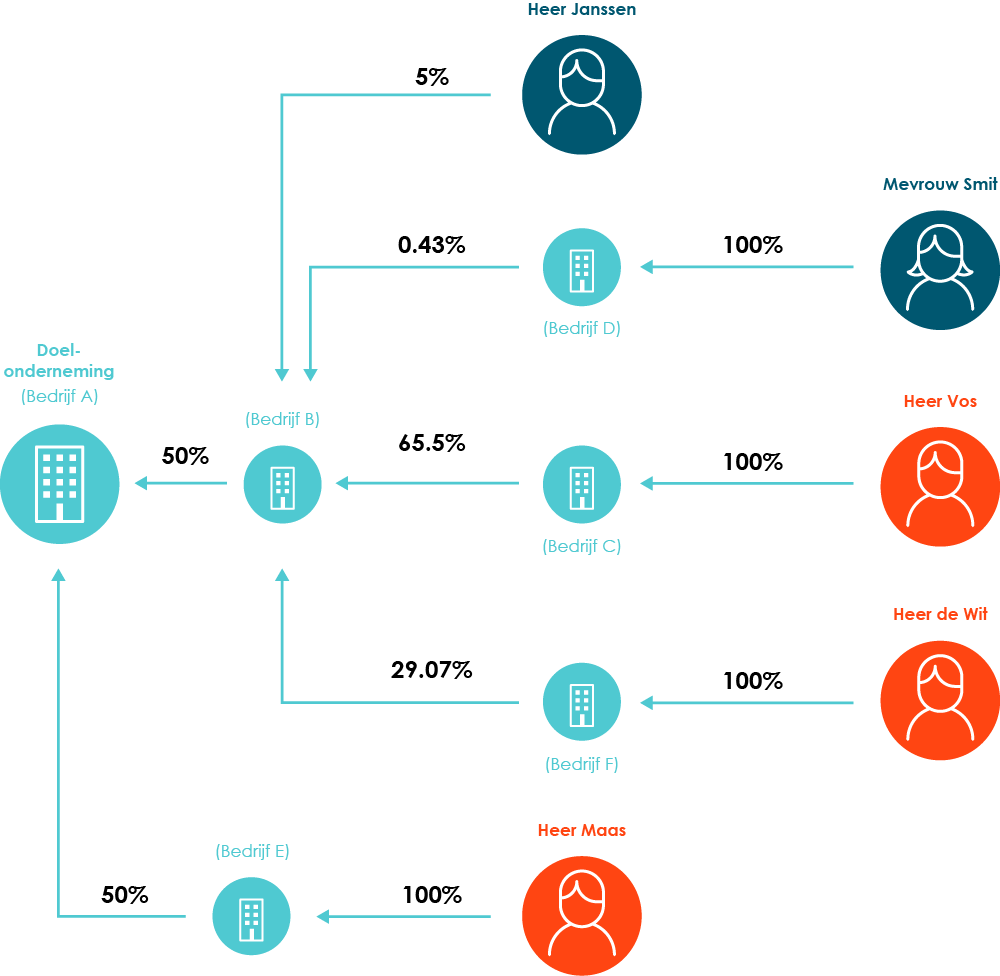

Circular relationships (indirect shareholding on multiple levels)

A data-inspired UBO approach

The traditional group structure approach would fail for multi-level indirect shareholding. This is because there is not one global parent, but two entities with an equal share of 50%. To accurately verify and calculate actual ownership, it is essential that the available data connects both global concern structures and personal share ownership. This can be done

The most common approach is to bring workflow and content together through Application Programming Interface technology. This speeds up the the data collection process enormously and ensures that workflows can be built correctly. This allows for immediate processing and for complex cases to be quickly routed to the right teams. Instead of calculating the UBO via online business intelligence reports and spreadsheets, the analyst creates a query for the business entity in question via the API. In this way, he initiates an analysis of the direct, indirect and circular ownership structures of the business entity, knowing within seconds who the relevant the relevant shareholders and what their ownership percentage is. It also becomes possible to build a notification methodology for ownership changes. This will free up resources to focus on the right customers and investigate important changes.

The most common approach is to bring workflow and content together through Application Programming Interface technology.

In this way, you create a supply chain of relationship data that speeds decision making and increases organizational efficiency. But a data-inspired approach has other benefits. Besides a lower risk of reputational risk from engaging with potentially flawed PEPs, companies can reduce the number of errors caused by manual input, Improve company-wide knowledge management as well as improve competitiveness by reducing operational costs.

Beneficial ownership recommendations

- Use API technology to build direct processing for onboarding and KYC.

- Make smart use of change detection within a target entity or entities belonging to a beneficial ownership structure. Alerts that recommend repeating a customer survey minimize the time it takes to conduct full surveys. Respond to changes immediately and you end up spending much less time.

Conclusion

The challenges are great, but data analytics are easing the pain of beneficial ownership identification. Through the use of technology and on-demand, timely, accurate and reliable data sources that provide information about global

Ultimately, the benefits of a data-inspired approach can only be realized by partnering with a respected data provider capable of verifying large amounts of information - obtained through a reliable, transparent data supply chain. The "all necessary means" test is a regulatory minimum standard, but with relevant and high-quality data that is shared company-wide shared, organizations can go beyond compliance. To become more agile and improve competitiveness.